A step towards integrated Met data

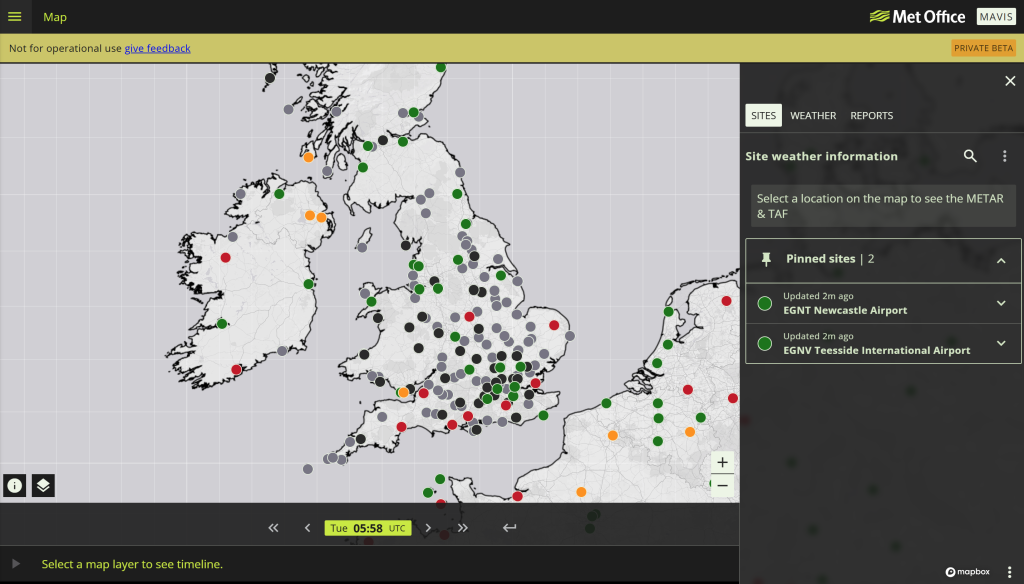

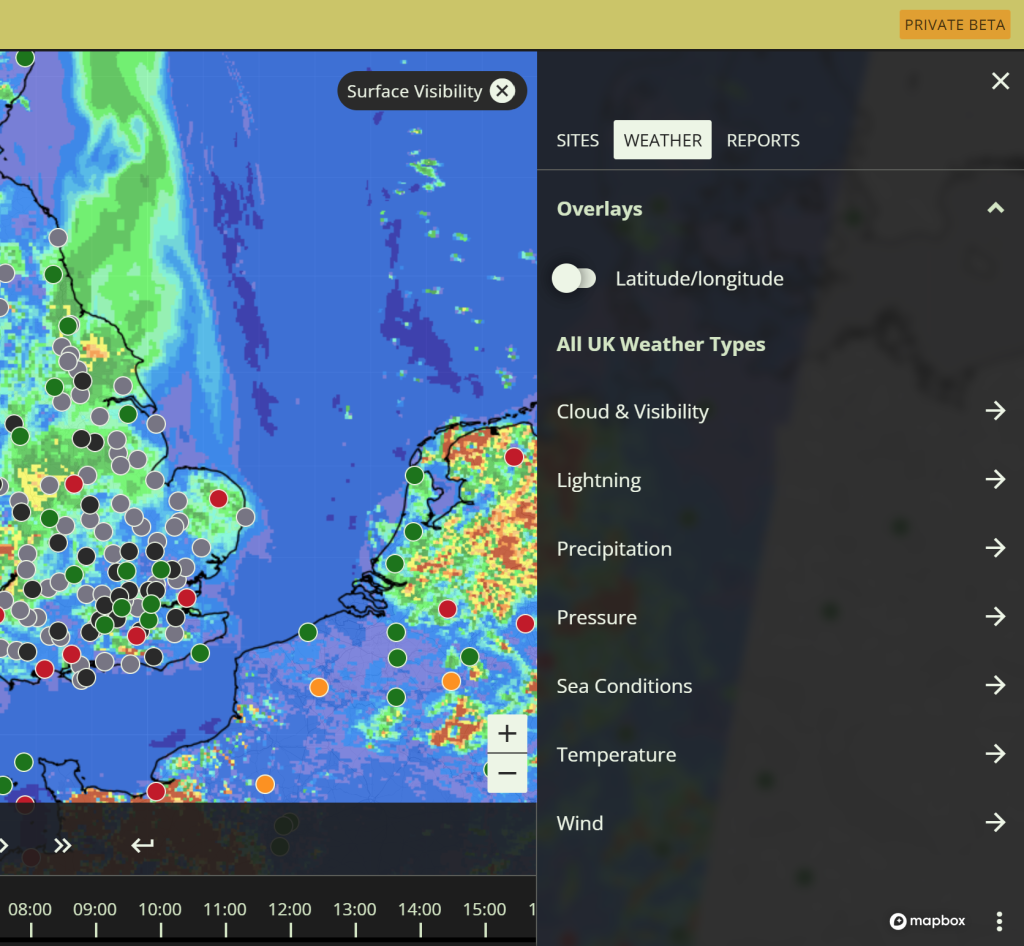

The Met Office has started rolling out the Met Office Aeronautical Visualisation Service, or MAVIS. It brings together four separate services into one place: Aviation Briefing Service, Network Weather Resilience, HeliBrief and OpenRunway. With a single login you can view METARs, TAFs, UK charts and configurable map layers for both planning and day-of-operation decisions.

MAVIS sits in beta today and is not approved for operational use during the development and dual-running period. Treat it as a preview rather than your legal or operational source. That said, it’s a great time to jump in and look at the features.

I’m genuinely impressed with what I’ve seen so far (despite some expected Beta issues) and whilst I won’t be hanging up my premium Windy account just yet, it certainly has a secure place in my future planning rituals.

What is genuinely new

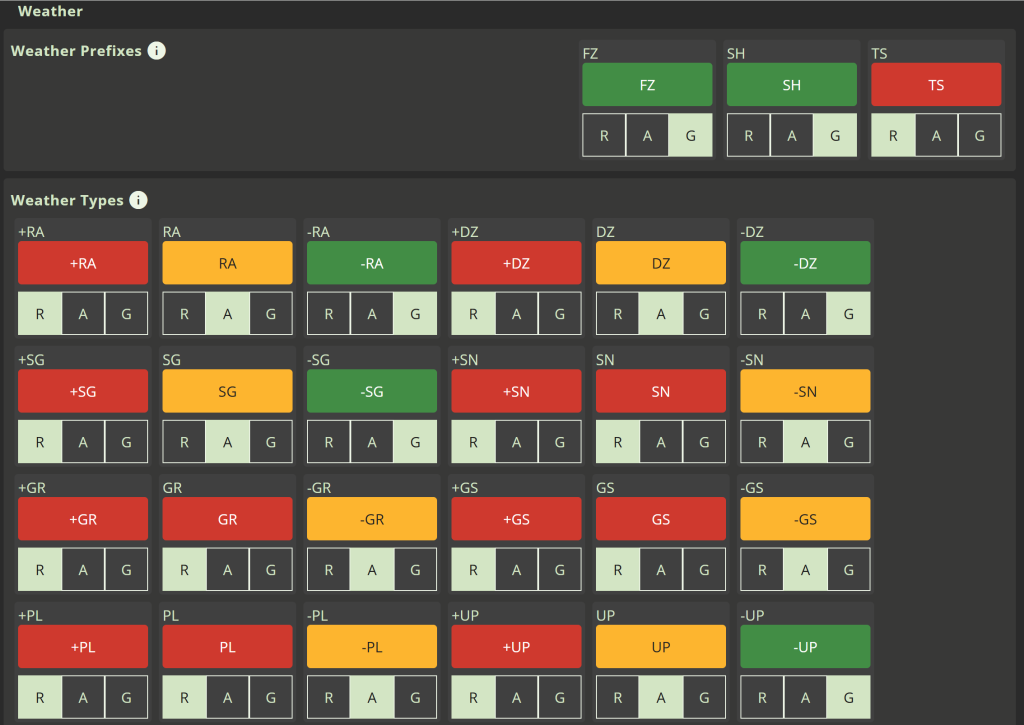

Two things stand out: modern visualisation and personalisation, something previously unseen in MetO offerings. MAVIS adds Red-Amber-Green thresholding on TAFs and METARs so sites can flag when your pre-set limits are breached. You can pin locations, save base maps, and bring in layers such as observed lightning or sea-surface temperature as they arrive. UK and near-Europe SIGMETs now display inside the portal. Each feature looks small, yet together they speed up the process of a good met review before every flight and when connected to the internet, will allow swift conditions updating in flight.

For offshore helicopter operations, MAVIS matters because HeliBrief is on the same retirement path as ABS and NWR. The aim is a single interface where deck decision makers, flight dispatch, and crews all see an aligned picture with the same thresholds and highlights. That is a better human-factors outcome than juggling portals at 05:30.

Timelines and the small print

ABS and NWR are scheduled to retire in Spring 2026, with transition into MAVIS beginning in Autumn 2025. If you rely on the free ABS for GA flying, note that ABS Premium will not be replicated at initial MAVIS release. The Met Office plans an equivalent in 2026 but has not given a firm date. For now, ABS remains available and Premium continues at £24, with the service ending in March 2026. Plan your switch and avoid surprises during check-rides or club trips.

Airports and airlines using OpenRunway should expect the same migration window. The headline remains the same: one platform instead of many, with OpenRunway functionality absorbed into MAVIS before Spring 2026.

Why this consolidation makes sense

Putting planning, situational awareness and alerts in one place reduces clicks and the risk of divergent interpretations. MAVIS supports mobile use (although its currently buggy on some platforms), custom layouts and pinned sites. For smaller operators and GA, a single, consistent interface lowers the training burden for new pilots and club members. For airports and offshore teams, one shared display improves collaboration when thresholds tip into amber or red. I can see this being a real benefit in winter North Sea operations.

Where to be cautious

Do not swap your operational briefings over yet. MAVIS is not an operational source during beta and dual running. Keep using ABS, NWR, HeliBrief or OpenRunway as appropriate until the formal cutover. Expect some data and layers to appear or change as access controls firm up, and expect adjustments in what individual users can see as the service hardens. I truly hope, for the GA community, that the Met Office keep high data levels free and acessible – if there is a user group desperately in need of accurate data its the GA flier.

Practical actions to take this month

- Map your workflows. Write down how you brief today and identify what MAVIS will replace. If you run offshore or airport operations, capture who sets thresholds, who owns watchlists, and who sends notifications. For the GA flier, think about your self briefing process. For me, it currently runs General Synopsis, F214, F215, GAMET and then to Windy. How will this process change?

- Freeze your minima and thresholds. MAVIS makes it easy to encode the limits you already use. Agree those values now so your team does not tune to taste later. If you’re a GA pilot and don’t have met limits, now might be a good time to think of them.

- Train to the visual language. RAG thresholding, pinned sites and layered maps will change how pilots scan. For training providers, build short sims or tabletop exercises that teach where to look first, then standardise that scan.

- Budget and access. If you or your club relies on ABS Premium features, note the gap before a MAVIS premium tier arrives. Keep ABS credentials valid until your first successful operational day on MAVIS.

The bigger picture

MAVIS is not just a fresh coat of paint. It is the Met Office pulling regulated and commercial aviation weather tools into one consistent experience, with a stronger focus on human-centred design. If the production version stays honest to the beta and retains the useful features we have seen so far, this will land well across GA, airports and offshore operations. The prize is faster decisions with less friction, which is exactly what you want when the cloud base is sliding and the deck is getting wet.